Early pioneers: The Struben Brothers

How was gold discovered in Johannesburg? Many of the pioneers of the South African interior suspected that there was gold here somewhere – it had, after all, been found a few hundred kilometres to the east, in Barberton. Some prospectors spent years buying up land, digging and panning, finding tell-tale yellow traces, but nothing substantial. In 1882, Siegmund Hammerschlag, whose farm Tweefontein lay where Krugersdorp is today, erected the first ore-crushing machinery, a two-stamp battery.

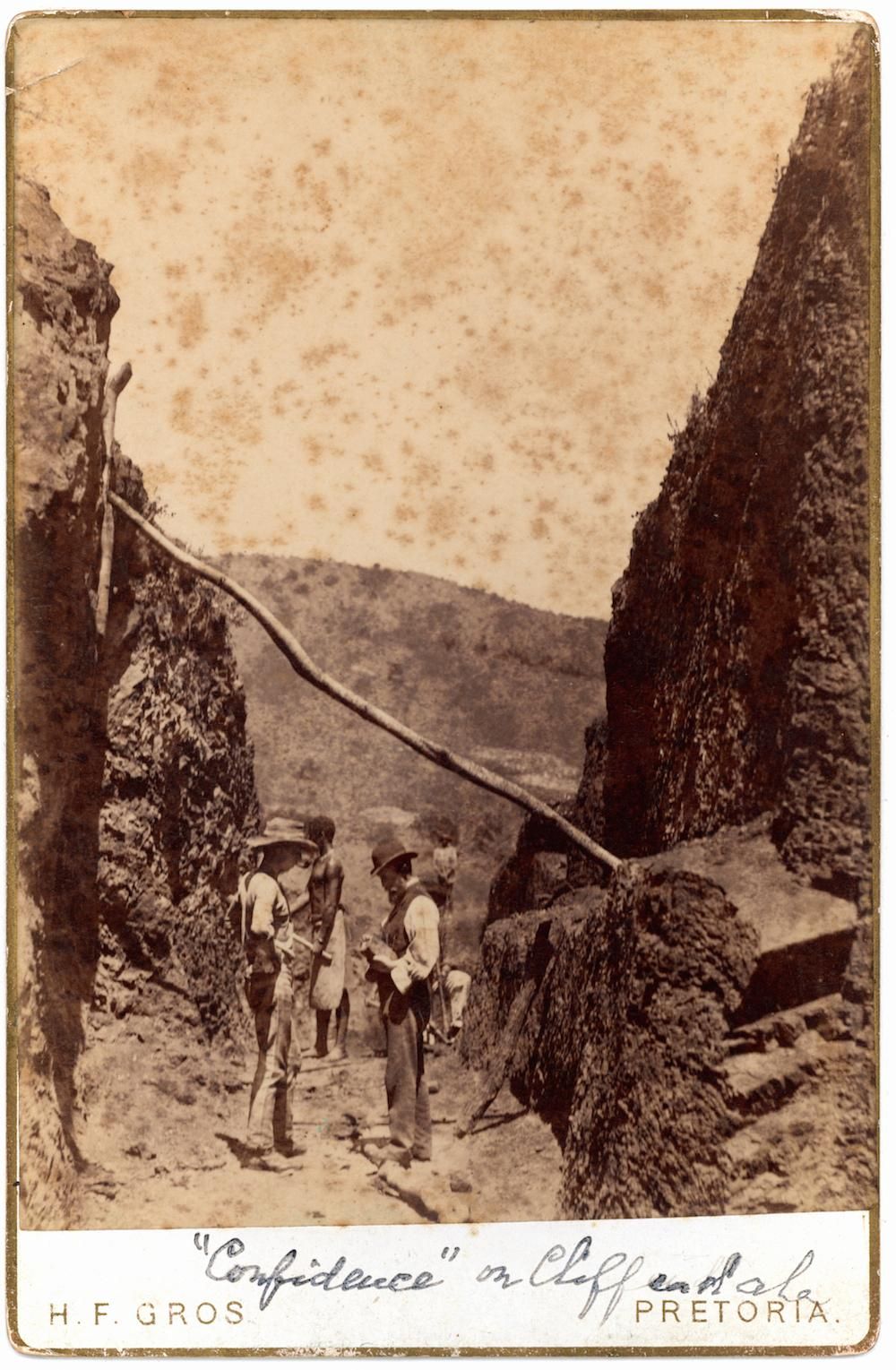

The first to strike gold were the Struben brothers, Fred and Harry, who owned parts of the adjoining farms Sterkfontein and Wilgespruit in what is now Roodepoort. They found what looked at first to be the first “payable” seam in 1884, and called their mine Confidence Reef, a name that proclaimed that the long search was over. Alas, even Confidence Reef lasted no more than a year.

The Struben family had immigrated to South Africa from Germany around 1840. In 1856, Harry bought his first span of oxen and became a transport rider between Durban and Pretoria. In 1862 he bought a farm in Pretoria, where he settled, with his wife and seven children. Fred also moved to Pretoria, where he worked as an assistant to Harry.

Fred Struben discovered gold at the Confidence Reef Mine – but his luck didn’t last long

The two brothers joined the rush to Kimberley, when diamonds were discovered there in 1871, but returned shortly afterwards when Fred’s health suffered. In 1882 Fred tried his luck again at Barberton in what is today Mpumalanga, where a rich but short-lived gold reef had been discovered. He returned to his brother’s farm, which was close to ruin after a hailstorm destroyed his crops.

Almost broke, the brothers considered emigrating to New Zealand, but a chance visit changed their minds. Knowing that Fred had a reputation for expertise in geology, neighbouring farmer Louw Geldenhuys arrived to ask for an opinion of the rocks on his farm Wilgespruit, which covered part of what is today the western flank of Johannesburg.

Geldenhuys had also been in Barberton, and he believed the rocks on his farm were similar to the gold-bearing rocks he had seen in Barberton. The two men rode over to Wilgespruit and looked at the rocks, and Fred became convinced that the area was indeed gold-bearing.

Fred made the astute observation that many of the pebbles appeared water-worn, which indicated that at some point in the distant past, “the whole area must have been submerged”, resulting in the accumulation of layers of sediment and “conglomerate beds … which might possibly carry gold as in other parts of the world”. (Quoted in: Early Johannesburg, It’s Buildings and People, by Hannes Meiring, Human & Rousseau, 1985).

Soon afterwards, Harry bought the neighbouring farm Sterkfontein, which had been advertised as having “gold-bearing quartz reefs”. Fred rolled up his sleeves and got to work.

Historian Eric Rosenthal, in his Gold! Gold! Gold! The Johannesburg Gold Rush (MacMillan, 1970), quotes Fred Struben as saying: “In January 1884 I started prospecting on the Sterkfontein farm at the west end of the range. The second day I found a reef showing gold, which assayed on the surface 6 penny weights, and at 50 feet had improved so that the sum had reached nearly 2 ounces.”

Fred kept finding “colour” – minute traces of gold – but none that amounted to much. He turned his attention to the neighbouring farm Wilgespruit, the eastern portion of which his brother had bought, and there established the Confidence Reef Mine.

The government of the Boer republic, the Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, headed by President Paul Kruger, watched these developments with anxiety. On the one hand, Kruger needed the taxes he could raise from gold exploration, and the gold taxes from Barberton were running low. On the other hand, he was wary of a gold rush bringing in thousands of foreign speculators, and of the interest the British might take in his tiny country if payable gold were found. The British had already made one failed attempt to annex the country, in 1877.

The Kruger government dithered, caught in a quandary. Kruger visited the area where the Strubens and others were digging, to gauge the strength of opinion.

In June 1885 Harry Struben made a presentation to Kruger and members of the Volksraad, or parliament. According to a report in the Dutch newspaper De Volkstem, Harry argued that the government should “foster the mining interests . . . He trusted that the Volksraad would so revise the gold law that proprietary rights would be fully defined, and no excessive duties levied to cripple the mining industry . . .”

But already the Struben’s find, Confidence Reef, was running dry. The Strubens had not found the main gold reef – that honour went to others who were also on the trail of gold. Yet once again, the Strubens played a role, because it was three of their workmen, inspired by the Strubens, who made the critical discovery.

One of Johannesburg’s distinctive mine dumps, scattered around the area south of the city

What became of the Strubens?

The Struben brothers made enough money from their find to enable them to retire not long after the main reef was discovered.

Harry, the business brain behind the pair, stayed long enough to be appointed the first president of the Chamber of Mines in 1887. In 1889 he retired to Cape Town, and lived in a suburban mansion until his death, at the age of 75, in 1915.

Fred retired to a large estate in Devon in England in 1888. He died at the age of 80 in 1931.

The first real gold diggers on the Rand

John Davis, a Welshman, discovered gold near Krugersdorp in 1852, but when he showed it to President Andries Pretorius, he was ordered out of the country.

A year later Pieter Marais, who had gone to California and Australia in search of gold, discovered alluvial gold in the Jukskei River which runs out of Johannesburg. He was allowed to continue with his search but was threatened with death if he revealed the discovery. He lived because his discoveries ran dry.

Confidence Reef

A strange disturbance among rocks on a hillside caught the eye of Fred Struben, one day in 1884. He and his brother Harry had spent years prospecting for gold on their farms 60 kilometres north of the Vaal River.

The Strubens were not the only people who had bought farms on this drab and treeless plateau, less because they had faith in the soil, than because they were convinced that gold ores were to be found here. Gold had already been discovered to the east, in Barberton. The rock here looked very similar. Scores of prospectors had been patiently panning for gold in this area for years – without success.

Fred Struben discovered gold at the Confidence Reef Mine – but his luck didn’t last long

Struben clambered the hill, broke off a piece of the disturbed strata of rocks, crushed and panned it. A teaspoon of gold appeared in his pan. He and his brother named the find the Confidence Reef Mine.

Years later, Fred was to write an article for the Rand Daily Mail, describing his moment of triumph: “Suddenly I looked up against the southern range, and saw that a disturbance had taken place in the rocks. I immediately conceived the idea of the possibility of a reef in that formation. The thought gave me new life and vigour. All depression and tiredness left me, and I moved quickly forward to the spot. I was not wrong in my opinion for there I found a reef cutting right through the displaced strata.

“Hastily I broke off a piece of the surface rock, and took it to a stream nearby which ran down the valley only some fifty yards away. I crushed the stone on a large flat rock, slipped it into the pan I always carried with me and panned it . . . Imagine my joy, when, out of that little bit of rock, there came almost a teaspoonful of gold, the pan being literally covered with it.”

One of the samples revealed an incredible result: 913 ounces of gold in one ton of rock. Fred said: “The gold permeated the quartz and was visible all through.”

Alas, Confidence Reef did not quite live up to its name. The gold was in quartz rock, which contains flashes of gold and other minerals, rather than long-term, payable rock. As Fred’s article explained: “After this first discovery, however, all trace of it was lost, and further prospecting failed to locate its destination.” The Confidence Mine lasted for a year before it ran dry.

Most prospectors of the period were working on quartz rock. But what they needed to tap into was a “banket” or conglomerate, which most prospectors were not familiar with and did not yet recognise. Banket is a Dutch word, used because the rock resembles a Dutch sweetmeat. A banket indicates a deep, payable reef.

But Confidence Reef Mine, nonetheless, is where Johannesburg’s history as a city of gold began. It was declared a national monument in 1984. The remains of the mine are still visible, inside the Kloofendal Nature Reserve, in Roodepoort, on the western flank of Johannesburg.

It’s a pleasant 500 metre walk from the car park to the diggings, a series of shallow caves and pits in the side of a koppie. The diggings can only be visited by appointment. Phone the Roodepoort Museum on 011 761 0225 to arrange a guided tour.

The Witwatersrand

The name ‘Witwatersrand’ means “white waters”, but there are no prominent white waters around Johannesburg. The name refers to an optical illusion caused by quartzite, a white rock found on the Witwatersrand. Seen from a distance after rain, quartzite rocks look like glistening water. The rock also contains pyrite which is visible as gold specks, hence the name “fool’s gold”.

Gold tour

The Parktown and Westcliff Heritage Trust does a tour of the city’s remnants of gold prospecting, several times a year. It takes in the head gear at Langlaagte where the first gold was found, the Crown Mines village south of the city, and the Chamber of Mines building in the CBD. Phone 011 482 3349 to find out when the next gold tour takes place.

Three Georges strike paydirt

Who discovered Johannesburg’s main gold reef? We know where the discovery happened, and more or less when it happened. What we don’t know is who actually made the discovery.

Johannesburg mushroomed from nothing into a tented town of several thousand inhabitants within a matter of weeks of its proclamation in October 1886, and none of those eager to strike it rich were much interested in who could take credit for the discovery.

Not until the late nineteen thirties, when Johannesburg had become the world’s largest and richest gold mining area, did public curiosity focus on the issue, and a commission was appointed by the Historical Monuments Commission, chaired by a senator, assisted by university experts on history and geology. The task was not an easy one – almost all the key witnesses were long dead. The commission’s report, delivered in 1941, did not settle the issue – instead it aroused huge public controversy, unresolved to this day.

The only point of agreement is that the discovery hinged on three men, all called George, and all employed as labourers building cottages on two neighbouring farms, Langlaagte and Wilgespruit. Langlaagte covered the area now occupied by such suburbs as Mayfair, Fordsburg and Sophiatown. Wilgespruit covered part of what is today Roodepoort.

George Walker, George Harrison and George Honeyball had varied backgrounds but all were drifters in search of the yellow metal. Walker was born in England where he had been a coal miner before immigrating to Kimberley, had a spell of fighting in the Zulu War in KwaZulu-Natal, then prospected for gold at Pilgrim’s Rest in Mpumalanga, where gold had been found in 1871. When coal was found in the Free State he became a coal miner again, and that’s where he met George Harrison.

Harrison, although an Englishman, had been a “gold digger” in Australia before arriving in South Africa. Tall and taciturn, his past was a mystery, but he was generally believed to have got into undisclosed trouble.

Walker and Harrison decided to leave the Free State and head to Barberton in the hope of changing their luck. In the vicinity of Johannesburg, they discovered that the Struben brothers, who had recently discovered gold at what they called the Confidence Reef (despite the name, it would run dry within a year), were hiring help. Walker got himself a job building a new cottage for the Strubens, close to their mine workings. Harrison got himself an almost identical job at a neighbouring farm, building a cottage for the Widow Petronella Oosthuizen, owner of the Block D section of the farm Langlaagte.

The moment of discovery

Walker’s account, as described by historian Eric Rosenthal in his 1970 book Gold! Gold! Gold!, is that on a Sunday in February 1886, he walked across the veld from Wilgespruit to Langlaagte to call upon his friend Harrison. Strolling through the long grass, he stubbed his foot upon an outcrop of rock, which he recognised as “banket”, or gold-bearing rock. Fetching his prospector’s pans he crushed a sample, mixed it with water – and spotted the unmistakeable “tail” of gold.

Rosenthal is sceptical of this account. It seems improbable to him that Walker could recognise the value of “banket” – a formation whose gold bearing qualities were still unknown at that time. But it is Walker’s rather appealing version of the discovery of gold that was accepted decades later by the Historical Monuments Commisision report, and entered local mythology as the accepted account.

Meanwhile, Struben, whose Confidence Reef was drying up, laid off his staff. Unemployed yet again, Walker, who appears to have done nothing about his sensational find, called on Harrison at neighbouring Langlaagte. Precisely what the two discussed is unknown; but what is clear is that on 12 April 1886, they signed a contract with another of the Oosthuizen clan, Gerhardus Cornelius Oosthuizen, who granted the pair the right to prospect for gold on his own portion of Langlaagte, Block C. Clearly the men knew they were on to something big, for Harrison immediately went to Pretoria to secure a one month prospecting licence. Oosthuizen, who was required by law to inform the state of any possible gold strike, wrote a letter to President Kruger himself, advising that “Mr Sors Hariezon” believed that “the reef is payable”.

Harrison never gave a description of his own discovery. But years later, historians discovered an affidavit by Harrison, written on October 12 1886, in which he claims full credit for the discovery on Gert Oosthuizen’s property, and describes how he had delivered a letter to President Kruger, who appears to have called him into his office and asked him what his credentials were. Harrison said he was an experienced gold digger, who had worked on the mines in Australia. Another affidavit from Harrison supports this: dated July 24th, it is a statement to the Mines Department which concludes: “I have long experience as an Australian gold digger and I think it is a payable goldfield”.

Certainly, the state was willing to accept the Harrison version – supported as it was by Oosthuizen – and it was he who was named the “zoeker” meaning discoverer, which entitled him to a free claim.

Gerhardus Oosthuizen and wife who owned a portion of the farm Langlaagte where gold was discovered

Harrison’s claim is supported by a number of respected historians. Ethel and James Gray, who did the bulk of the research for the commission, and discovered the Harrison affidavits, came out on Harrison’s side. So did retired judge F Krause, who wrote his own exhaustive examination of the evidence in 1946.

The government official charged with responding to Gert Oosthuizen’s letter was Kruger’s close adviser Dr WJ Leyds, who was to become intimately associated with early Johannesburg. He added a tart note to the letter that the payability of the gold had not been proved, but the matter could not be ignored. Leyds’ nephew, the historian GA Leyds, who drew heavily on his uncle’s reminiscences, leaves no doubt as to whose side he was on in his 1964 book ‘A History of Johannesburg’ (Nasionale Boekhandel):

“One afternoon, probably in June or July, around five o’clock in the afternoon, the two (Harrison and Walker) were walking in an easterly direction when George Harrison saw an outcrop of conglomerate or quartz on a rock ledge. He examined it carefully, then fetched his prospector’s pick-axe and struck off some pieces of the rock. He seems to have had this rock crushed and panned at the Strubens’ mill north of what is now Roodepoort.”

But there was a third George as well, whose accounts, much more detailed than the others, appear to support Walker. George Honeyball was the nephew of Widow Oosthuizen, and lived on her farm, where he worked variously as a blacksmith, carpenter and general handyman, never quite managing to make a living. He met the other two Georges while helping to build the Struben and Oosthuizen cottages, with Harrison and Walker doing the masonry, and Honeyball doing the carpentry.

According to Rosenthal, Honeyball recounted that on Sunday morning, February 7th 1886, he was in Mrs Oosthuizen’s home when Walker arrived with his sample of banket. “He borrowed my aunt’s frying pan in the kitchen, crushed the conglomerate to a coarse powder on an old ploughsare, and went to a nearby spruit where he panned the stuff. It showed a clear streak of gold.”

The next day, Honeyball persuaded Walker to show him where he had found the rock, close to the boundary between the widow’s portion of the farm and her cousin Gert’s. Honeyball traced the line of the reef back into his aunt’s farm, and six hundred metres away from Walker’s spot, he found a similar outcrop of rock. He broke off a piece, and got a prospector working on a neighbouring plot to pan it for him. There was gold in it.

The prospector offered to pay Honneyball to tell him the secret of where he had found the gold, which he did, to Walker’s great annoyance. Nor did the prospector keep his mouth shut. Word of the discovery spread with extraordinary speed. Two days after Harrison’s visit to Kruger’s offices, the government telegraphed the local magistrate, asking him to verify the claims. It was already too late – gold diggers were flooding the territory, and had drawn up a petition, signed by 73 men and delivered on July 26th, calling for gold fields to be proclaimed. Kruger had no choice.

At 9am on 20 September 1886, prosecutor and gold commissioner Carl von Brandis stood beside his wagon and read in Dutch the proclamation made by Kruger, to several hundred diggers:

“Whereas, it has become apparent to the government of the South African Republic that it is desirable to proclaim the farms named Driefontein, Elandsfontein, the southern portion of Doornfontein, Turffontein, the government farm Randjeslaagte, Langlaagte, Paardekraal, Vogelstruisfontein, and Roodepoort, all situated on the Witwatersrand, district of Heidelberg, as a public digging.

“Therefore I, Stephanus Johannes Paulus Kruger, state president of the South African Republic, advised by and with the consent of the executive council, in terms of Section 5 of Law Number 8 of 1885, as amended, proclaim the above-named areas as a Public Digging in the following sequence and as from the following date, to wit . . .”

But what happened to George Walker and George Harrison? Neither grew rich from the discovery. Harrison sold his “discoverer’s” rights almost immediately, for just ten pounds. He disappeared a month after the diggings were proclaimed, while involved “as a witness in an unsavoury court case involving a native woman,” according to an early historian of Johannesburg, LE Neame.

The Australian government is known to have asked the Kruger government to find a fugitive named George Harrison, wanted for embezzlement. Some say Harrison left for Barberton, but was killed by lions. An old prospector claimed years later to have gone to Barberton along with Harrison, who died there and was buried at Kaapschehoop, but no evidence has been found.

George Walker also soon left the Rand, returning many years later to lay his claim to having discovered the main reef. He was given a pension by the Chamber of Mines and lived in a house in Krugersdorp until his death at 71 in 1924. But there are many who dispute his story. Krause described Walker as a “heavy drinker and a bluffer”, who only began to make his claims to the discovery late in life. GA Leyds notes in his history, as proof of Walker’s unreliability, that he received four hundred pounds in compensation for phthisis – but his post-mortem revealed no signs of the disease.

How did the gold get here?

Researchers from the University of Arizona reported in the journal Science in September 2002 that the gold welled up from the earth’s core some 3 billion years ago, making it more ancient than the Witwatersrand’s rocks, which are 300 million years younger. The suggestion is that the gold actually surfaced somewhere else, and was gradually washed into the Witwatersrand Basin by ancient rivers.

The orthodox theory is that the Witwatersrand Basin, some 350 km long and 200 km wide, was the site of an ancient sea around 2,75 billion years ago. Rivers running through gold-bearing hills – which may have been common in the ancient earth – washed sediments of sand and gravel – and specks of gold – on to the bed of this sea. Gradually they built up a 7 km thick layer of ore-bearing conglomerate rocks. There was little oxygen in the earth’s toxic atmosphere at the time, life was restricted to bacteria and primitive algae in the seas, and volcanic eruptions and meteor impacts were common.

It was volcanoes and meteors that extinguished the ancient seas and rivers – but ensured the survival of the gold. The sea appears to have died some 2,7 billion years ago, when massive volcanic activity in the area caused a layer of lava to cover the basin.

Then another catastrophe occurred 2 billion years ago – a ten kilometre wide meteor struck the earth in the region where the small town of Vredefort is today, some 100 kilometres south of Johannesburg. The impact vaporised 70 cubic kilometres of rock, and created a crater 250 to 300 kilometres in diameter. The debris thrown up by the impact covered the Witwatersrand. The blanket of debris was so thick that it preserved the gold from a further 2 billion years of erosion – which is why gold is still found here, and is rarely found elsewhere.

Today the gold-bearing “reef” forms a swathe of parallel ridges some 100 kilometres long from east to west, roughly centred on Johannesburg. The gold is buried far below the surface, and is mined at depths of up to 3,6 km. This means, ironically, that although the Witwatersrand is as high as 1,5 to1,8 km above sea level, the deepest mines run as much as 1,8 km below sea level.

Over 40 000 tons of gold have been mined on the Witwatersrand, and a similar amount is believed to still lie underground. But extracting that gold requires ever-deeper mining of ever-poorer ores, in a time of declining gold prices. In 1999, for example, it was estimated that it cost US$222 to mine an ounce of gold in South Africa, against $189 in the US and $169 in Canada. Gold mining in South Africa hit its peak in 1970, when over 1 000 metric tonnes were mined, generating US$1,16 billion in sales

Photo: https://goodthingsguy.com/business/south-africa-gold-resource/